The Forbidden Fruit – Gambling in China

Many card and board games are believed to have originated in Ancient China. Some of these games involved betting and gambling and they have been an inherent part of the Chinese leisure culture for centuries.

This changed when the Communist Party seized power in 1949, declaring gambling a “corrupt, feudal practice” and hence strictly banned by law.

When the Reform and Opening-up policy was introduced in China in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the authorities have somewhat released their strong grip on gambling and card games. Gaming and carding parlors (known in Chinese as 棋牌室, literally meaning “chess and card rooms”) sprang up in every street corner and card games and private betting among groups of friends thrived. Despite this, gambling remained illegal outside the two national lotteries (the China Sports Lottery and the China Welfare Lottery) and these establishments were far from satisfying the crave.

What do you do when your Favorite Pastime is Forbidden by Law?

Travel to Casino Hubs Abroad

A partial solution was found overseas. Chinese gamblers have flocked to casinos around the globe and went to neighboring Hong Kong to participate in horse race betting. And then there was Macau – with the help of the Chinese government, the former Portuguese colony just across the border from Guangdong Province has become the world’s largest casino center, surpassing Las Vegas since 2006.

Another casino hub attracting hordes of Chinese gamblers in recent years is the Philippines, where the hosting and entertainment industry, catering to the needs of the Chinese, was booming until the outburst of Covid-19 pandemic. This is manifested in job openings in the Philippines for Chinese nationals, many of which re published in dubious online platforms, such as QQ and Telegram groups dedicated to gambling and fraud as well as in Chinese-language underground forums. Another negative side to this craze is gambling-related crime, which has escalated in the Philippines over the past years.

However, traveling abroad is not accessible to everyone in China with a crave for gambling and even those who do travel, cannot always travel as often as they’d want to. There was a market rip for solutions, and with travel restrictions following the outburst of Covid-19 pandemic, this market’s potential grew even larger.

From Casino Hubs to Online Gambling Arenas

they satisfied the Chinese gambling community for about a decade. Since then, China has outlawed online gambling as well and the active websites are also situated offshore, on servers located outside the country.

These online casinos, gaming websites and gambling arenas cause a big headache to the Chinese Communist Party. If a decade ago the authorities have largely turned a blind eye to this phenomenon, nowadays, with the clear aim to promote a “civilized, harmonious society”, China sees it as a challenge and tries to fight these online platforms. Of course, these moral considerations, important as they may be, are dwarfed by the financial problem, as online gambling is draining hundreds of millions of yuan out of the country. Yet China is finding it hard to stop websites that are registered and operated abroad, especially when the hosting counties, such as the Philippines, are not so keen on cooperating.

Enter Cybercrime

The size of the market is a huge business incentive, creating more and more actors and fierce competition. These online casinos use various methods in order to lure more gamblers onto their websites. One of these methods, is fraud. For example, one of the common frauds that takes place is when fake gambling websites pretend to be official sites of famous casinos in Macau.

But competition does not stop there. In order to gain bigger chunks of online traffic, gambling websites fight and attack one another, and their weapon is – ironically – online traffic.

Chinese Gambling Website Posing as Macao’s Venetian Official Online Casino

The DDoS Fighting Ring

Chinese hackers are more than eager to lend a helping hand. As most state-sponsored cyber activities handled by patriotic hacking groups from the early 1990’s until about a decade ago, are now under the wings of the Chinese intelligence apparatus, many idle hackers have turned into cybercrime, looking for easy profit. This type of cybercrime is mostly directed inbounds.

One of the ways in which Chinese hackers are involved in the online gambling industry is by breaching online casinos and gaming websites, stealing their user data and selling it on Darknet marketplaces or offering it on designated QQ and Telegram groups.

Sample from a Gambling Site Database Leak,

Offered for Sale on a Chinese Darknet Marketplace

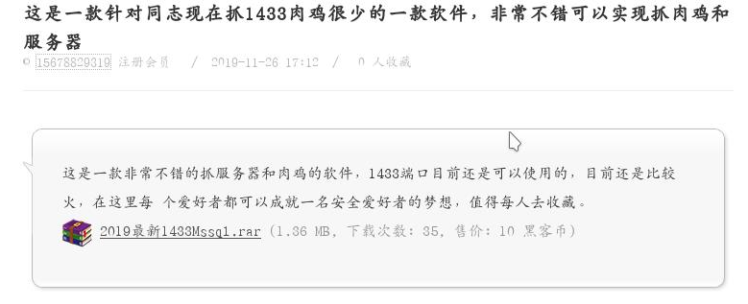

Another way, which drives a whole underground sector of cybercrime in China, is by conducting DDoS attacks against competitors. These attacks take the gambling websites down and thus, hopefully, drive their customers to the gambling site that ordered the attack.

DDoS has also become a popular weapon for pornography websites and Darknet marketplaces, who launch DDoS attacks against each other. For example, China’s largest online marketplace on the Darknet, has experienced a large-scale DDoS attack during the summer, disrupting its activity for several weeks.

Flashing Ads on a Chinese Hacking Forum, Offering Tailor-made DDoS Attacks,

among other Hacking Services

The DDoS Chain

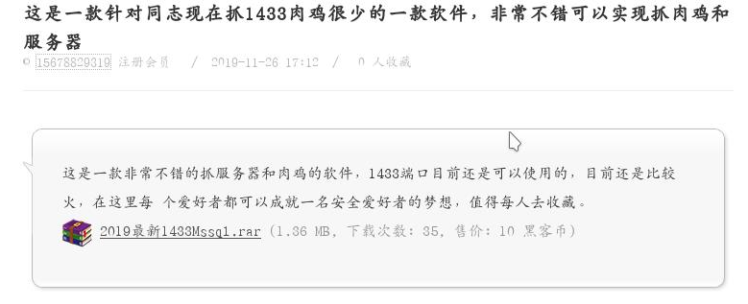

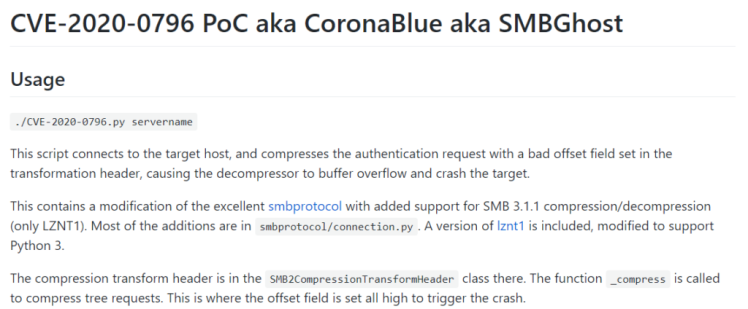

The first step in a DDoS attack is to gain control of a large number of computers and other online devices and to turn them into bots, in order to divert huge traffic to the attacked website and thus shut it down. In Chinese hacking slang, these computers are named “broilers” or “meat chickens” (肉鸡). Members of Chinese underground hacking forums constantly offer tools for detecting these “broilers”, namely scanners that trace vulnerabilities in computers and servers. These tools allow the attacker to penetrate these vulnerable devices, implant trojans in them and hence control them remotely. The tools are referred to in Chinese as “Chicken Catchers” (抓鸡) and hackers who operate on those forums trade them between themselves.

‘Broiler’ Detection Tool Offered on a Chinese Hacking Forum

In addition to buying tools to detect “broilers”, DDoS attackers can also buy these “broilers” directly, as these are sold in bulks on forums and designated QQ/Telegram groups. Based on the number of messages in forums and chat groups, of people requesting to buy “broilers”, it is quite clear they are in high demand.

The customers of the “broiler” market are in turn becoming the suppliers of DDoS attacks and offer their tailor-made services online. Whoever orders the attack can contact the attacker via private messaging, define the target and agree on a price according to the length of the attack and the nature of the attacked website. According to a report published by the Chinese tech firm Tencent, this is what the chain of custom-made DDoS attacks looks like:

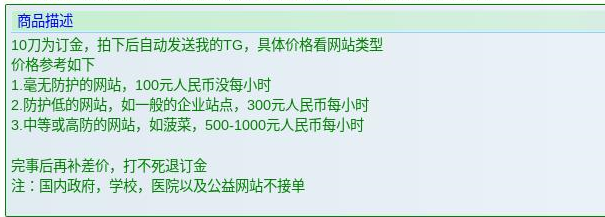

The Offer: DDoS as-a-Service

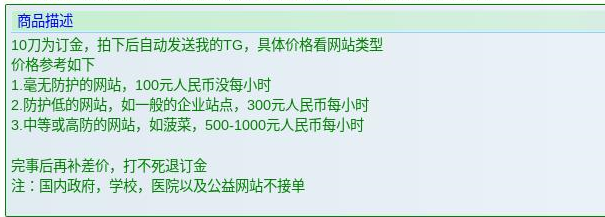

The screenshot below, showing an offer posted on a prominent Chinese Darknet marketplace, can shed light on the how these DDoS as-a-service transactions are conducted. It also demonstrates what kind of websites are legitimate targets and which websites are off-limits, for fear of being prosecuted by the authorities. The post reads:

DDoS as-a-service Offer Posted on Chinese Darknet

Translation:

Hunting Down Cybercriminals

Chinese law enforcement authorities are well aware of this problem and are relentlessly trying to crack down these cybercriminals and their activities. In late 2018, a man in his twenties from Suining County, Jiangsu Province, was arrested by local authorities, after discovering he had implanted a malicious code, which allowed him to remotely control a local server. During his investigation, he admitted to being part of a team of at least 20 hackers from all over the country that had used “broilers” in order to conduct DDoS attacks by demand.

The team had been involved in more than a hundred DDoS attacks, harming or controlling more than 200,000 websites and earning more than 10 million yuan along the way. Members of the team were arrested across China, yet this only emphasized the magnitude and popularity of the DDoS and DDoS as-a-Service markets, and the success of taking down this cybercriminal operation was merely a drop in the ocean.